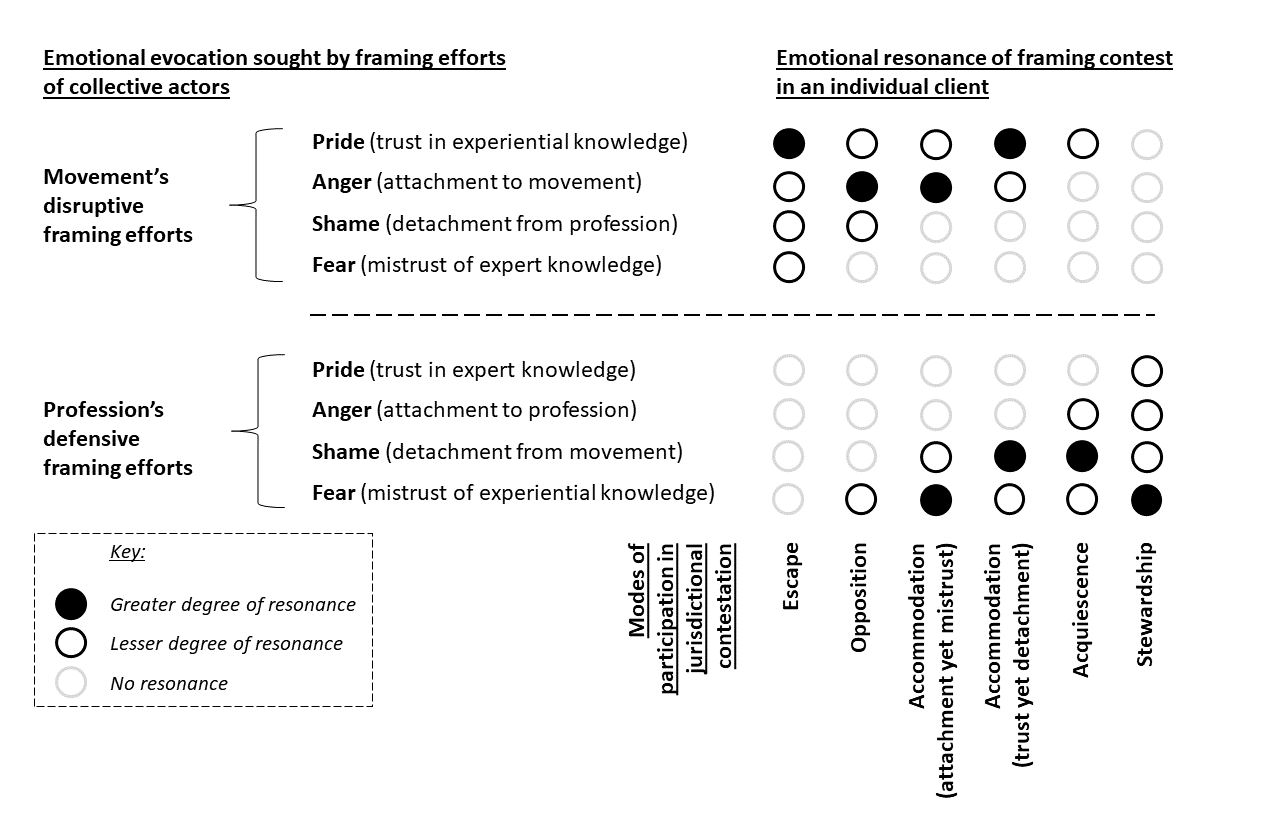

| Framing efforts that evoke emotions successfully | Emotional resonance | Mode of participation in jurisdictional contestation |

|---|---|---|

| Only the social movement’s framing efforts are successful | Pride in supporting alternative project (greater degree), anger at profession, shame of complying with profession’s prescriptions, and fear of relying on established arrangements (lesser degrees) | Escape: Seeking to withdraw from established arrangements for a peer-driven alternative |

| Both framing efforts are successful to some degree, but the social movement’s framing efforts dominate (some ambivalence) | Anger at profession (greater degree), shame of complying with profession’s prescriptions and pride in supporting alternative project yet fear of relying on it (lesser degrees) | Opposition: Seeking to radically transform established arrangements |

| Both framing efforts are successful to a comparable degree (full-fledged ambivalence) | Pride in supporting alternative project but shame of deviating from profession’s prescriptions (greater degrees) and anger at profession yet fear of relying on alternative project (lesser degrees) or anger at profession but fear of relying on alternative project (greater degrees) and pride in supporting alternative project yet shame of deviating from profession’s prescriptions (lesser degrees) | Accommodation: Seeking to incrementally improve established arrangements |

| Both framing efforts are successful, but the profession’s framing efforts dominate (some ambivalence) | Shame of deviating from profession’s prescriptions (greater degree), anger at social movement and fear of supporting alternative project yet pride in supporting it (lesser degrees) | Acquiescence: Seeking to passively accept established arrangements |

| Only the profession’s framing efforts are successful | Fear of relying on alternative project (greater degree), shame of deviating from profession’s prescriptions, anger at social movement, and pride in supporting established arrangements (lesser degrees) | Stewardship: Seeking to actively reinforce established arrangements |

Before describing and illustrating each mode, we emphasize the role of felt ambivalence in shaping client participation in jurisdictional contestation. Research on social emotions highlights the prominence of ambivalence in episodes of contestation ( Citation: Creed, DeJordy & al., 2010 Creed, W., DeJordy, R. & Lok, J. (2010). Being the Change: Resolving Institutional Contradiction through Identity Work. Academy of Management Journal, 53(6). 1336–1364. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2010.57318357 ; Citation: Meyerson & Scully, 1995 Meyerson, D. & Scully, M. (1995). Crossroads Tempered Radicalism and the Politics of Ambivalence and Change. Organization Science, 6(5). 585–600. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.6.5.585 ) . ( Citation: Ashforth, Rogers & al., 2014, p. 1454 Ashforth, B., Rogers, K., Pratt, M. & Pradies, C. (2014). Ambivalence in Organizations: A Multilevel Approach. Organization Science, 25(5). 1453–1478. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2014.0909 ) defined felt ambivalence as “simultaneously positive and negative (…) actor’s alignment or position with regard to [an] object, where a positive orientation means attraction or a pull toward it and a negative orientation means repulsion or a push away from it.” ( Citation: Meyerson & Scully, 1995, p. 588 Meyerson, D. & Scully, M. (1995). Crossroads Tempered Radicalism and the Politics of Ambivalence and Change. Organization Science, 6(5). 585–600. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.6.5.585 ) wrote that ambivalence “stems from the Latin ambo (both) and valere (to be strong)” and implies the “expression of both sides of a dualism.” Full contestation of, and support for, a profession’s jurisdictional control are ideal types that represent opposite ends of a continuum. Empirically, we argue that it is common for clients exposed to an episode of jurisdictional contestation to experience various degrees and forms of ambivalence—i.e., most clients neither fully embrace or repudiate the movement’s aspirations nor the profession’s jurisdictional control.

For instance, a client may feel angry at a profession for its perceived breach of duty and therefore inclined to support contestation, yet also feel afraid of relying solely on a movement’s alternative institutional project to address their needs, which would temper their support ( Citation: DeCelles, Sonenshein & al., 2020 DeCelles, K., Sonenshein, S. & King, B. (2020). Examining Anger’s Immobilizing Effect on Institutional Insiders’ Action Intentions in Social Movements. Administrative Science Quarterly, 65(4). 847–886. https://doi.org/10.1177/0001839219879646 ) ; ( Citation: Kish-Gephart, Detert & al., 2009 Kish-Gephart, J., Detert, J., Treviño, L. & Edmondson, A. (2009). Silenced by fear:The nature, sources, and consequences of fear at work. Research in Organizational Behavior, 29. 163–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.riob.2009.07.002 ) . In other instances, a client may feel proud of supporting the alternative project promoted by the movement, but also ashamed of deviating from the profession’s prescriptions ( Citation: Gould, 2009 Gould, D. (2009). Moving politics: emotion and act up’s fight against AIDS. The University of Chicago Press. ; Citation: Britt & Heise, 2000 Britt, L. & Heise, D. (2000). From shame to pride in identity politics. InStryker, S., Owens, T. & White, R. (Eds.), Self, identity, and social movements.. University of Minnesota Press. ) . Thus, we argue that felt ambivalence profoundly shapes how a client participates in jurisdictional contestation.

Building upon this argument, we theorize five distinct modes of client participation in jurisdictional contestation. In developing our modes, we sought a continuum that not only connected extreme and opposite client reactions to the framing contest but was also informed by the insights, detailed above, that challengers emphasize pride and anger while incumbents emphasize fear and shame, even if both sides seek to evoke all four emotions to some degree but in different ways.^[We are grateful to our reviewers for encouraging the symmetric treatment of both sides of the framing contest as concerns emotions sought for evocation.] So, we began with the intent of identifying one mode for each situation in which one of these emphasized emotions, i.e., the types of pride and anger sought by the challenger movement and the types of fear and shame sought by the incumbent profession, had strong resonance and for which the action taken by a client could be causally linked to it. Next, we anchored the two ends of our continuum on full success for each side in the framing contest in terms of achieving resonance of the emotions they sought to evoke. These steps led us to “escape” and “stewardship”. We then incorporated ambivalence by considering situations where one side had minimal but non-zero success across the four emotions sought for evocation in terms of achieving resonance, which led us to “opposition” and “acquiescence”. This step led us to realize that we also needed to consider situations where both sides were equally successful across the four emotions sought for evocation and where two strongly resonating emotions pulled in divergent directions, which led us to two distinct types of “accommodation”.

At each step in which we settled on a mode, we complemented our theoretical moves with considerations of the empirical support that we could find in research describing social movements disrupting the jurisdictional control of health-related professions. By interrogating this research, we noted that, indeed, more and less successful framing efforts by a social movement (and, conversely, a profession), defined in terms of achieving strong, some or no resonance of the emotions it sought to evoke, empirically mapped to different modes of client participation and different constellations of emotions experienced by clients. Although other configurations of emotional resonance and possible actions taken by clients are imaginable, this step of triangulating our theoretical inferences with empirical evidence gave us confidence in the ones which we included in our model―of which Figure 1 provides an overview.

Escape and stewardship represent the two least ambivalent modes of client participation, with each at opposite ends of the continuum of supporting movement or profession, respectively. The opposition, accommodation, and acquiescence modes are shaped by different forms of felt ambivalence where the framing efforts of both movement and profession resonate to some degree in clients. We illustrate each mode with examples from health-related work domains.